Finding ways to engage AAC learners is important to professionals across disciplines and service delivery settings.

In today’s post, we feature guest author Kate McLaughlin, who is an SLP serving individuals with AAC needs in Connecticut. She shares a perspective on building engagement through the perspective of meaning making.

“Motivating” Emergent Communicators through Shared “Meaning-Making” & Communication Responsibility

Are you a speech-language pathologist (SLP), teacher, or parent supporting an emergent AAC learner? Maybe you are just starting AAC with a learner who has a complex profile (for example, significant motor impairments, difficulties with motor planning, and/or sensory processing differences)? Maybe you have a learner who has learned to ask for some favorite things, but is not communicating beyond that? Do you struggle to “motivate” them? You’re not alone. I’ve met many kids who have been described as “not motivated to communicate.” I’ve also met many parents and professionals who want to help them expand their skills, but don’t know how.

What do we mean when we call a learner “emergent?” An emergent AAC learner is one who does not yet have a reliable means of symbolic expression (Dowden, 1999). In other words, they have not yet established a way to express themselves through language. They may not yet understand language or they have a well-developed understanding of language without a way to express themselves. Either way, the very nature of being emergent means that they don’t yet have the skills to tell us all their thoughts or the things they find interesting. So how do we figure out what “motivates” them to communicate at a deeper level?

Let’s start with what motivates anyone to communicate. I communicate to express my wants, needs and ideas. But more than that, I communicate to feel seen and to build relationships with others. All of our communication exists in relationship to others. Interaction is integral no matter how simple or complex. Our emergent learners are no different.

Erna Alant (2017) talks about communication as the “meaning making” that happens between two people. She describes it as a process of understanding each other, but also connecting emotionally. She stresses that it is the foundation of relationships. Her concept of meaning making relates to the idea of “co-construction,” which you will find more frequently in the AAC literature (Solomon-Rice & Soto, 2011; Hörmeyer & Renner, 2013). Co-construction refers to shared or “joint-creation.” (Jacoby & Ochs, 1995, p. 171) In the case of communication, co-construction is the shared understanding that develops between two people when they interact with each other.

In short, communication is not just the language that is produced for a listener. It is the sum of an interaction between two people in which they connect emotionally and experience shared understanding. We all do it every day. We do it when we make eye contact to greet someone passing by, when we order a coffee, and when we listen to the events of our family member’s day. Can you think of other examples? It can be fleeting or long-lasting, but it is two people connecting and understanding one another. Is this possible for our emergent communicators? It’s already happening, more than you might think.

Even before our learners have a robust AAC system, they are communicating. They are sharing themselves with the world using the strategies they already have. They may use gestures, eye gaze, body movements, facial expressions, vocalizations, laughing, crying, among others. These are the moments that need our attention.

In these times, our learners are beginning to take communicative responsibility. A learner takes communicative responsibility when they work to express their own message to a partner who does not know what they want to say (Brekke & von Tetzchner 2003, p. 210). In order to engage in meaning making, we need to catch moments when our learners have something to say that is worthy of taking communication responsibility. It must be something important to them and something that needs to be communicated because we don’t know it. And therein lies the motivation. When it’s their own message, they are already motivated. When it’s their message, it’s more likely to get their full attention. When it’s their message, it’s worth the effort it will take to express it. When we engage with them in those moments and connect emotionally we are “meaning making.”

Let’s consider some examples…

The first interaction is between Liam, his mom, and a therapist. Liam was 10 years old at the time. He has a diagnosis of autism. Liam’s communication was primarily through facial expressions, vocalizations, body language and a limited number of pictures used to request food items. He had just received an iPad with Proloquo2go (Intermediate Crescendo) and was in his first few weeks of use. This interaction occurred in an early training session with the child’s mom.

Context: Afternoon at home, after school

Though this child was not yet using his device, he was communicating and his partners were sensitive to his feelings and perspective. The motivation was his need to get outside, move his body and recover from the demands of the day. His communication initiated the interaction. The therapist was able to verbally reference his actions to increase everyone’s awareness of his communication. She modeled language that was relevant to the context and child’s perspective. In this interaction, there was a shared experience and understanding. Meaning making occurred in the back and forth. The child felt heard and a relationship of trust began.

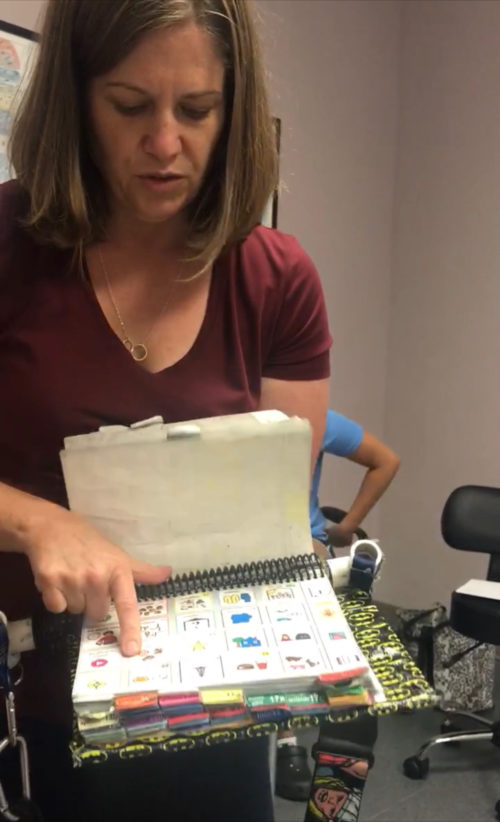

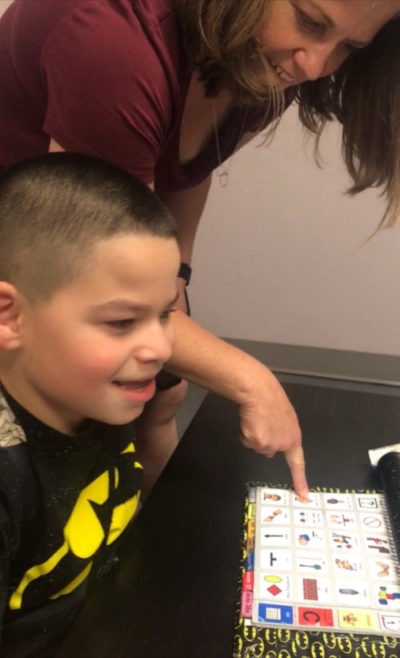

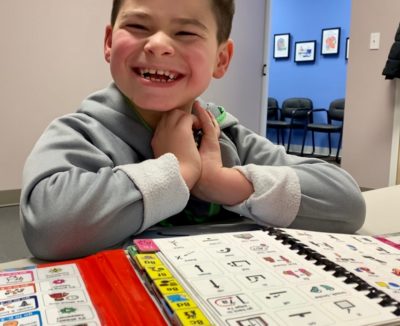

The next example is an interaction with a child named Joey. He has a diagnosis of Angelman Syndrome (Deletion+). At the time of this interaction, Joey was 8 years old. He was using a 20 Expanded Functions PODD book and PODD for Compass (15 School Age) on an iPad. Unlike the previous learner, he had established some symbolic expressive language using his system, but he communicated most consistently through facial expressions, gestures and body language. He was still largely emergent in his AAC use.

Here the sum of the interaction was a loving exchange between the parent and her son. This mother did not question her son’s meaning. She took in the context and responded. Was her interpretation accurate? It’s hard to say, but he accepted her response and stayed engaged. The back and forth provided the silly dynamic that this child loves. His initial thought and the enjoyment that followed were his motivation for communicating. It was not to get something or to engage in some contrived opportunity. It was real life and relationship. Through his mother’s modeling, this child also got to witness how additional language could be used to talk about and enjoy the moment. Even so, this interaction was so much richer than the language on the device could suggest.

So how do we make “meaning making” happen for our learners? First, we have to slow down, listen with all our senses and see what they are already communicating. Those are moments when they are initiating and starting to take communicative responsibility. They just don’t have the skills to make their messages clearer yet. When we really take the time to listen, we’ll be better able to determine the language that might help them communicate what matters to them. We can then model that language on their AAC, which we know is a central strategy for teaching AAC (Sennott, et al, 2016). Over time, we work to grow our meaning making interactions and expand the strategies our learners have to make themselves understood.

The most powerful meaning making opportunities will happen in unplanned moments. Most of our opportunities won’t happen in a speech session. They happen in life. They are unexpected and messy, but that’s where the most valuable learning can happen. This means communication must be an absolute priority, especially for all team members working with a student in school. It can be challenging, but it’s absolutely essential. Speech-language pathologists are needed to coach all communication partners not only on the AAC system but also on how to engage in the dance of meaning making. We have to meet our AAC learners at their current level of communication when they have something to say. We need to provide ongoing aided language input and do the “teaching” in response to what they are already expressing. We need to remember that communication is multimodal and no one form is better than any other. When we do this, meaning making is possible even for our most emergent learners. In these moments of meaning making, we find the motivation that our learners already have and harness it to provide them with the most powerful learning opportunities.

1 CAPITALIZED words in example interactions indicate words modeled on the child’s AAC system.

References

Alant, Erna. (2017). Augmentative and alternative communication: Engagement and participation. San Diego: Plural Publishing

Brekke, K. M. & von Tetzchner, S. (2003). Co-construction in graphic language development. In S. von Tetzchner & N. Grove (Eds.), Augmentative and alternative communication: Developmental issues (pp. 176-210). London: Whurr.

Dowden, P. (1999). Emerging communication, Augmentative and Alternative Communication at the University of Washington, Seattle http://depts.washington.edu/augcomm/03_cimodel/commind2a_emerging.htm

Hörmeyer, I., & Renner, G. (2013). Confirming and Denying in Co-Construction Processes: A Case Study of an Adult with Cerebral Palsy and two Familiar Partners. Augmentative and Alternative Communication, 29(3), 259–271. doi:10.3109/07434618.2013.813968

Jacoby, S., & Ochs, E. (1995). Co-Construction: An Introduction. Research on Language and Social Interaction, 28(3), 171–183. doi:10.1207/s15327973rlsi2803_1

Sennott, S. C., Light, J. C., & McNaughton, D. (2016). AAC Modeling Intervention Research Review. Research and Practice for Persons with Severe Disabilities, 41(2), 101–115. doi:10.1177/1540796916638822

Solomon-Rice, P., & Soto, G. (2010). Co-Construction as a Facilitative Factor in Supporting the Personal Narratives of Children Who Use Augmentative and Alternative Communication. Communication Disorders Quarterly, 32(2), 70–82. doi:10.1177/1525740109354776

About the Guest Author

Kate McLaughlin, M.S., CCC-SLP, is a speech-language pathologist specializing in augmentative communication for children with complex communication needs. She is passionate about supporting children and families on their journey to autonomous communication. She is a certified member of the American Speech-Language and Hearing Association and holds licensure as a speech-language pathologist in the state of Connecticut. Kate is in private practice in Connecticut (AAC Services of CT) providing direct therapy and consultative services for individuals with complex communication needs. She posts on Facebook and Instagram as The AAC Coach. More information is available at www.theaaccoach.com.

Financial Disclosures: Kate is self-employed through her private practice, AAC Services of CT. In this role, she receives compensation for therapy, consultation, training and speaking services.

This post was written by Carole Zangari